Strengthening the safe harness of the present moment is essential to help trauma survivors face and leave their painful behind them.

John, my client, is weeping. Sobs grip his body. The sound of them, and his posture, tell me that John is dissociated from his present moment self – a 55 year old man, and successful real estate agent who is years ahead of the trauma he lived through.

John,” I say, “Let’s focus on the present moment together. You are experiencing some very big emotions right now. I want to make sure that you are in the driver seat. Together we can help the scared little boy inside you, but not if he takes over the strong, capable person who you are right now.”

The foundation of effective trauma treatment begins with resourcing. During the resourcing phase of treatment, survivors of trauma use mindfulness practices to teach their bodies that they are safe in the present moment. As neuroscience on trauma confirms, a consistent focus on safety in the present moment can reduce debilitating symptoms, such as overwhelming emotions, flashbacks, nightmares, anxiety, and hypervigilance.

Within a secure therapeutic relationship, clients can remain present while tracking their level of activation within their Window of Tolerance (WoT). Combined with resourcing, awareness of the WoT helps trauma survivors to develop clarity that the trauma is behind them, so they can reclaim a sense of safety, and move on with their lives.

FROM SURVIVAL MODE TO DUAL AWARENESS

John experienced early childhood trauma that left him in a state of high alert. While the traumatic circumstances that John survived were years behind him, he came to treatment to resolve symptoms such as disruptive bodily sensations, nightmares, anxiety, a pervasive sense of danger, and difficulty developing trusting, intimate relationships.

Though being on high alert helped John to survive early childhood trauma, in his current life it caused John to feel exhausted, and prone to illness and depression. Trauma survivors like John find relief when they can distinguish between past trauma, and safety in the present moment. This is known as dual awareness which is the ability to observe and recognize that an internal experience of distress belongs to past trauma but that they are safe in the present moment.

THE NEUROSCIENCE OF THE WINDOW OF TOLERANCE

A big part of my work with John was to help him become aware of his WoT, and to help his body learn that the danger was behind him, and in the present moment he is safe.

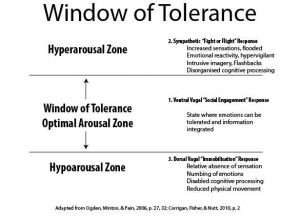

The WoT is a helpful visual framework which illustrates how the nervous system is impacted by trauma.

The Window of Tolerance (WoT) is a helpful visual framework which illustrates how the nervous system is impacted by trauma.

During trauma, our prefrontal cortex (PFC), the part of our brain responsible for helping us to reason, plan, and regulate intense emotions, goes offline and more primitive survival strategies at either the top, or bottom of our WoT take over.

At the top level of the WoT is hyperarousal which refers to the state of fight or flight, such as rage or fear. At the bottom of the WoT is hypoarousal. In animals, hypoarousal is a survival strategy in which prey feign death to deter a predator. Both hyper and hypo arousal are physiological survival mechanisms dictated by the limbic system, specifically the amygdala.

The centre of our WoT is where we are the most resilient to stress. This is the zone where in the face of a stressful situation we can remain calm, and make wise decisions. Choice is only possible within the centre of our WoT because in the upper and lower levels, our PFC goes offline, and automatic survival behaviour takes over.

Being in the centre of the WoT is also necessary to take in new information, learn, and be open to give and receive love and affection. While in a life threatening situation, our brain and nervous system are designed to prioritize survival over bonding behaviours. That being said, a warm soothing person whom we trust can help us to move from the upper and lower ends of our window, and into the centre where feel safe.

Seminal trauma researcher and originator of Polyvagal Theory, Stephen Porges, explains that we are wired to feel soothed and comforted by another person. This is the social engagement system. Its core is the vagus nerve which travels from the brain stem to the heart with linkages to the muscles that regulate the face and head, including those involved in vocalization, listening, facial expressivity, and gesture.

When caregivers are present to help us regulate our emotions, the vagus nerve shifts from hyperarousal, or dorsal vagal, to a ventral vagal response. This is the equivalent of moving out of fight/flight or freeze and into the centre of our WoT where we are the most resilient to stress.

For John, and for those negatively impacted by traumatic events, developing resources helps to strengthen the brain’s retrieval advantage for the centre of the WoT.

While each person’s journey to develop resources is unique, the PFC is strengthened when clients can step back, and connect with the present moment. This skill lessens activation in the amygdala, our brain’s threat detection system, and reduces trauma symptomology.

THE RESOURCE OF MINDFULNESS: FEELING SAFE TO FEEL SAFE

As Peter Levine states in his book, Healing Trauma, “Everybody has resources, and every body has resources”.

Resources are as diverse as people. Levine explains that resources can be external/internal or both, and can be anything or anyone that supports and nurtures a sense of physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual well being, such as nature, friends, family, animals, a spiritual practice, athletics, dance, movement, tai chi, martial arts, music, and other expressive arts.

Once John realized that he didn’t need to remain in the almost constant state of anxiety that had become his normal state of being, he was ready to develop resources. Rather than be at the mercy of old trauma memories, John made efforts to synchronize his nervous system with his current life, and goals.

For John, the experience of mountain climbing got him in touch with himself. On his bike John felt confident, vigorous, and free.

Using mindfulness, John learned to slow down, and harness the experience of mountain biking in his body and nervous system. By repeatedly strengthening his awareness of the sensations, and five sense perceptions (sight, smell, taste, hearing, and movement) of mountain biking, John increased his brain’s retrieval advantage for feeling confident and curious. This reduced the grip of old patterns, and freed his body from its tendency to flounder in old trauma networks.

INTERVENTIONS TO RECLAIM THE CENTRE OF THE WOT

Janina Fisher, a well respected trauma therapist and leader in the trauma field, states that our ability to reason, analyze, plan, learn from experience, and make meaning, lives in our left brain. Other leaders in the field of psychotherapy, such as Daniel Siegel, and Marcha M. Linehan, also distinguish between left and right brain.

There is a great deal of consensus among trauma experts that mindfulness helps those impacted by trauma to strengthen the PFC, and to deactivate limbic brain regions involved in perpetuating traumatic symptoms.

For John, and for many clients who struggle with trauma related symptoms, working with a therapist who is respectful, understands the physiology of trauma, and can help clients to track where they are within their WoT, can be life changing.

As John learned about the neuroscience of trauma, and used mindfulness to track his level of activation, John began to recognize when his amygdala was overfunctioning. Awareness of his WoT, and developing resources, helped to recruit John’s PFC in deescalating physiological activation.

When I notice John moving out of his WoT within a session, I intervene:

“John, I notice that your breathing has become shallow, and you haven’t looked up for some time. I’m wondering if now might be a good time to take a break from what we were talking about, and reconnect with here and now?”

Because every client is unique, experimentation is needed. A suitable intervention is time-sensitive, and fits the client in the moment. When combined with the presence of an emotionally attuned therapist, the right intervention can help a client move from hyperarousal or dorsal vagal, to ventral vagal in which the social engagement system is online.

My therapeutic tool box includes an array of mindfulness oriented choices, such as:

DBT’s pleasant moment calendar

5-4-3-2-1: Notice 5 things you can feel, 4 things you can see, etc.

Steele, van der Hart & Boon’s Learning to Be Present, Anchors, or Stress Reduction Exercises

The skills of Containment, and Pendulation, and others from Peter Levine’s book, Healing Trauma.

EMDR’s Calm Place, or Container Exercise

Emotional Freedom Technique’s (EFT) use of tapping on meridiens while using a calming affirmation

I have found that any of these interventions can be helpful but are not a substitute for a respectful, attuned therapeutic relationhip. As the research of Scott D. Miller in Escape From Babylon attests, a trusting, collaborative therapeutic relationship is more important than therapist allegiance to any model or formula. In order to move forward, clients need an understanding of the rationale for suggested treatment options to provide consent for decisions regarding the direction of therapy. Because trauma strips a person of their sense of control over their body and choices, restoring client empowerment through collaboration and consent is essential to successful trauma treatment.

FROM INSECURE TO SECURE ATTACHMENT WITH A SUPPORTIVE OTHER

For many survivors of developmental trauma, the ability to rely on another person for care and support is foreign. When the people who were supposed to protect and care for you were abusive or neglectful, the brain, nervous system, and sense of self is often wired to perceive caring individuals as dangerous.

When caregivers do not provide emotional support, or are neglectful or abusive, the social engagement system that lives in the ventral vagal gear of the vagus nerve is lacking. This is known as insecure or disorganized attachment, and its damaging effects on brain development, and mental health, are far reaching.

Without secure attachment, a person’s nervous system lives with an impending sense of danger. Rather than rely on the care and support of others to help regulate distress, fear, and the negative self concept that often lingers after trauma, can cause trauma survivors to fail to develop, or withdraw from supportive relationships.

In our earlier sessions, my expression of care could trigger John to spike or plunge into the upper and lower areas of his WoT. When John could step back and observe this phenomenon and understand its costs, he was determined to experiment with taking in emotional support rather than remain isolated from the warmth and intimacy he wanted in his life.

As Bruce Perry states:

“Fire can warm or consume, water can quench or drown, wind can caress or cut.

And so it is with human relationships: we can both create and destroy, nurture and

terrorize, traumatize and heal each other” (Perry, B., 2006, p.5)

The experience of caregivers who are neglectful or frightening wire the brain and nervous system in an insecure attachment strategy. The process of moving from insecure or disorganized, to secure attachment, requires that the nervous system create new neural pathways.This is known as neuroplasticity. Our brain is like plastic. It can change its structure in response to experience through the activation of neurons. In the same way that unpredictable, frightening caregivers can wire an insecure attachment strategy, a consistent, healing relationship that nurtures safety can rewire the brain for secure attachment.

As John made the realization that his trauma symptoms developed to help him cope with caregivers who were unpredictable, and at times frightening, he became more compassionate with himself.

Instead of being hard on himself, John realized that in the absence of caregivers helping him to feel safe, he had never learned how to soothe himself. As a result, running and fighting became John’s go-to strategies which had kept him strong and self reliant, but had also prevented him from learning to regulate his emotions in a healthy way.

Realizing that he could make his body his ally, John developed resources that empowered him to track, and intervene with triggers. Within a kind, reliable, neuroscience and trauma informed therapeutic relationship, John learned to ride the distressing waves of traumatic memory while remaining calm, and within the centre of his WoT.

SUMMARY

With the benefit of resourcing, survivors of trauma like John can develop skills to widen their WoT so intense emotions and physical sensations occur with less frequency. When these distressing experiences do arise, the use of resources helps to alleviate symptoms, and to regulate emotional distress. With the support of a therapist who is kind, compassionate, neuroscience and trauma-informed, clients can build new neural pathways for secure attachment that strengthen the left brain, activate the social engagment system, and release chronic overactivation in the amygdala. For clients who’ve been harmed and betrayed by neglectful or abusive caregivers, mindfulness-based, trauma-informed treatment can foster hope and healing within their lives and relationships.

References:

Siegel, D.J. (2012). Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc.

Fisher, Janina (2017). Structural Dissociation webinar

Levine, Peter (2008). Healing Trauma

Linehan, Marsha M. (2015). DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Perry, B.D., & Szalavitz, M. (2006). The Boy Who Was Raised As A Dog. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Get help with your trauma

I can help you find relief from disruptive symptoms, feel safe, and enjoy life again.